The office of the Commissioner of Police dates to 1865, when under the new Municipal Act of 1865, the senior officer of the police force was made solely responsible for the police administration of the city, with the title of Police Commissioner. This title was conferred on Sir Frank Souter – the first ‘Police Commissioner’ of the city. Even today, a bust of Sir Frank Souter sits on a pedestal in the halls of the Office of the Commissioner of Police at Crawford Market. The rich history of Bombay’s police force is known to few and its importance in understanding the evolution of law and order in the city cannot be stressed enough.

In 2018, the Tata Trusts were approached by the then police commissioner – Dattatray Padsalgikar – to guide in setting up a police museum, one that could compete with international parallels and showcase the rich history of the police force and the city. While in talks with the police force regarding this project, the existence of police records was made known to us. What also lies in the alcoves and cavernous halls of the Special Branch Office of the Mumbai Police are reams, bundles and stacks of police records. In addition there are also more than 80 digests that contain weekly letters from the Office of the Commissioner of Police, with the earliest one dating to 1914. These records contain information ranging from administrative day-to-day happenings, to detailed surveillance notes of nationalists / communists / mafia (as the decades progressed), to records of key city events (mill workers’ strike / bandobasts / shootouts), and more. It contains stories that, when creatively mined and presented, will fill the halls of a police museum for decades to come.

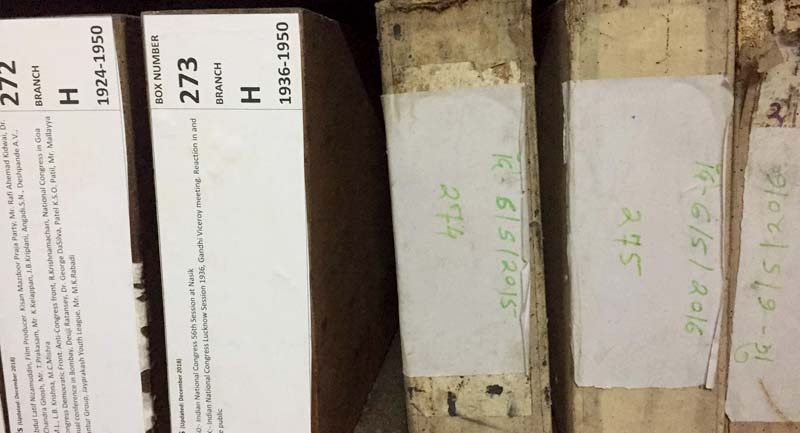

The paper records lie in a state of neglect, with dust, silver fish and humidity causing constant deterioration. The archive of the Special Branch Office, as it were, is a working archive – accessed, albeit not frequently, by the police officers for reference. It is also open to researchers, who can access it upon special request, but its existence is little known.

The existence of these important records, and the willingness of the police force to participate in its protection and documentation, helped shape a grant that was initiated in May 2018, to the newly instated Mumbai Police Foundation. Mumbai Police Foundation was to undertake a year-long project to set up the Mumbai Police Archives and a modest paper conservation lab. However, the core of this project comprises the training imparted to police volunteers in the best practices of conservation and archiving – this was considered prudent because of the volume and sensitive nature of the police archives. This would not only mitigate the expense of engaging external consultants for a long period of time, but would also instill a sense of ownership and history amongst the police staff, which will go a long way in helping preserve the records.

At the initial stage of the project, digitisation of the records was decided against, till police readers could go through the files and categorise the importance of the documents. Instead, it was mutually agreed that training will be imparted to a select team of volunteers in manual archiving and documentation, and simultaneously, another larger team of volunteers would be trained in paper conservation. Two expert organisations were engaged to train police volunteers in the workflow of paper conservation (HIMSHACO, Nainital) and of documentation and cataloging (Eka Archiving Services Pvt. Ltd., Delhi). Till date, 30 volunteers have been trained – 26 in paper conservation, and 4 in archiving. Regular assessments are carried out by the mentors who ensure that the teams are equipped to handle the workload when the Trusts exit from the project in October 2019. Some statistical highlights of the project include the treatment and binding of 87 digests, archiving the contents of 940 wooden boxes and 95 tin boxes (ongoing process), dry brushing and indexing material of up to 80 cloth bundles, and the setting up of a modest paper conservation lab. A procedures manual, in English with certain crucial sections and formats translated into Marathi, has been prepared for the archiving team. It is a step-by-step guide on how to handle and document the paper records. A similar manual will be prepared for the conservation team by the end of the project. The remaining weeks of the project will focus on re-housing of the archives and setting up a secure management structure in place so that the archiving and conservation teams are able to run the project independently.

What has been remarkable about the project is the learning trajectory of the police volunteer teams – from lackadaisical and obligatory, to hesitant yet intrigued, to immersive and enthusiastic, to knowledgeable and curious, to now adept and secure in their training and interest. However, what remains a concern as the project comes to a close is the management of the two teams and the continuance of their work with the same rigour and pace as has been established painstakingly over the past year.

If managed well, with a sound administrative structure in place that can dislodge procedural bottlenecks, and an enthusiastic and well-trained in-house team, this project has the potential of being presented as a replicable model across state institutions that house similar rich archives.

— Paroma Sadhana