“When my child was a year old, our anganwadi worker (AWW) Guman Devi told me that my child was malnourished and in danger of falling ill,” says Mathura Devi of Doriya village in Rajasthan, who was taken aback at the news. When she asked how Guman Devi could know, the latter, along with Panchi Devi, the local accredited social health activist (ASHA), showed her the growth monitoring chart being maintained for her child.

Manorama Devi of Nagar village in Rajasthan has a similar tale. Her daughter was born with a low birth weight. As she grew older, she became weaker and would fall sick often. Initially, Manorama wasn’t too concerned. Then the local anganwadi worker Manju Paliwal visted Manorama along with Bhanwari Sharma, the auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM), and Chandrakanta, the local ASHA. They informed Manorama that her daughter was severely malnourished and needed care.

Rinku Mali is from Pachewar village in Rajasthan. Her second son was born healthy. Unfortunately, a severe bout of diarrhoea when he was ten months old made him sickly. He grew thinner by the day. Rinku spent a lot of money on medicines to no avail. And then the local anganwadi workers intervened – weighing her son and showing her the evidence against infant growth charts – to convince Rinku that her son was severely malnourished.

These are not atypical stories – these children are among the hundreds of thousands of children who suffer from malnourishment across the country. Fortunately, for the children mentioned above, the Tata Trusts’ ‘Making It Happen’ project intervened in their villages to provide them with immediate and adequate recourse.

The ‘Making It Happen’ project commenced in April 2018 in the Nagar, Doriya and Pachewar villages in the Malpura block of Rajasthan’s Tonk district. The objective was to demonstrate how multi-sectoral action would help promote nutrition among women and children. The intent was to show how this could be done by enhancing the quality of services that the state offers through anganwadis and the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme.

Simultaneously, the project focused on raising community awareness and demand for ICDS services such as growth monitoring, ante-natal care, supplementary nutrition, behavioural change communication and pre-school education. Home visits, community-level meetings and demonstration of diversified diets helped to raise awareness of the importance of nutrition at individual, household and community levels.

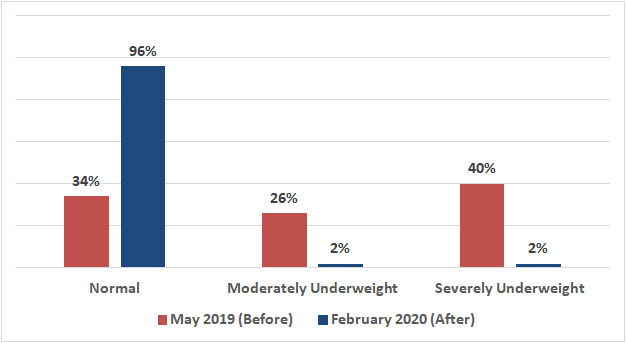

In May 2019, the project began to monitor the weight of 50 randomly selected children between the ages of 6 months to 2 years of age, so as to demonstrate to anganwadi workers and the community how nutrition can be promoted, and malnutrition treated, through simple interventions, such as regular growth monitoring, improving the diversity of diets consumed by children, and advice on the proper use of Take-Home Ration. (The Take-Home Ration is a nutritious powder that can be made into a gruel; it is distributed by the state government to young children and pregnant mothers through the anganwadi network.)

Among the target demographic, it was found that, of the 50 children selected for the project, 16 were of normal weight for their age, 13 children were moderately underweight, while 20 children were severely malnourished.

The results were tabulated and the project objectives discussed with the three sets of frontline workers — the AWWs, ANMs and ASHAs. A plan of action was drafted and frontline workers were trained in a number of key areas, such as early detection of growth faltering, especially wasting; the importance of nutrition during the 1,000-day window of opportunity; promotion of diet diversity, especially complementary feeding; and inter-personal communication techniques.

The three ‘A’s – the AWWs, ANMs and ASHAs – were given the responsibility of the regular weighing of the 50 children, joint home visits to the homes of severely undernourished children, counselling for parents and family members, weekly distribution of Take Home Rations, medical assistance when required, and regular medical check-ups for the severely undernourished children.

For instance, the frontline workers taught Mathura that it was necessary to supplement her breast milk with additional nutrition, and that she had to monitor her child’s weight every month. She was also taught how to cook the Take-Home Ration, to ensure that her child got fed more nutrients.

In Manorama’s case, a diet schedule using food available at home was developed for the child. Manorama was taught recipes using the Take-Home Ration, and she was encouraged to measure her daughter’s weight every 15 days. Rinku was given advice on diets, especially the importance of family food and the use of the Take-Home Ration powder.

A visible change was seen in as little as three months. The number of children who were of normal weight for their age had risen to 48 from 16 . One child was moderately underweight, and only one child remained severely underweight.

The project, met with success because of the three main reasons – co-ordination between frontline workers, consistent growth monitoring, and family counselling. Its success has given frontline workers a lot to think about – they now realise the benefits of collaborative efforts towards a common aim.

Mathura’s, Manorama’s and Rinku’s children have all benefitted greatly from the intervention. Taught to cook innovative recipes using the take home rations, Mathura’s child recovered and continues to be healthy. Manorama is full of praise for the three frontline workers who helped her cope. “I appreciate the loving care of these three women who never blamed me, but supported me at all times,” she says, gratefully. Her daughter is fine now, and is no longer falling sick. Rinku concurs, “They would call me every 15 days, and Parwati, the AWW, would enquire about progress practically every day,” she says. Rinku is now advising other women to visit the anganwadis to find a solution for their children’s health problems. The Trusts’ Make It Happen initiative is helping keep malnutrition at bay.