The Qutb Shahi Heritage Park in Hyderabad spread over 106-acres, is a unique ensemble of over 70 structures, including tombs, funerary mosques, Baolis (stepwells), Hamams (bathhouses) and archaeological remains.

In 2012, Tata Trusts partnered with Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) to conserve nine major monuments situated within the park. The vision was to preserve these 16th-18th century heritage monuments and transform the landscape into an accessible public space that reflects the culture and history of the region. The partnership ran for 8 years, from 2012-2020, during which time the tombs of Sultan Quli Qutub-ul-Mulk, Jamsheed Quli Qutb Shah, Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah, Mohammad Quli Qutb Shah, Abdullah Qutb Shah, Hyat Bakshi Begum; the Great Mosque, the Hamam and the Badi Baoli were fully restored and conserved.

The project was part of the Tata Trusts’ Arts and Culture portfolio, that looks to support projects on built heritage conservation as one of its focus areas. The Trusts’ past initiatives in this area includes partnerships with AKTC to conserve Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi (2008-2011), and the accompanying smaller monument, the Nila Gumbad (2012-2015); as well as the recently concluded project that supported the creation of a permanent exhibition at the Humayun’s Tomb Site Museum, highlighting the conservation efforts of Humayun’s Tomb, and the preparation of a Specifications Manual for conservation of built heritage.

Early challenges

This large-scale project was technically challenging, and each structure had to be studied and approached uniquely for its restoration and conservation. The AKTC team produced 2,500 drawings of plans, sections, and elevations, and documented each monument's condition, before the start of the project. A multi-disciplinary team of architects, engineers, archaeologists, historians and landscape designers were appointed to oversee the conservation works in the park.

One of the first set of challenges came in the form of a legal stay on the conservation works on-site due to a case filed by the Wakf Tribunal Board in 2013. A few months later when the western wall of the Badi Baoli collapsed, threatening the integrity of the monument, the stay was finally lifted and work began.

After desilting of the soil and removal of the fallen debris, the walls of the Badi Baoli were repaired using 70% of the stones from the debris. Meanwhile, a team of engineers and landscape architects examined the slopes and vulnerabilities that led to the collapse. Based on their findings, the path of the water flow was altered in a manner that does not impact the walls of the Baoli in the future. Previously, tankers were used to source water for conservation works and irrigation at the site. After its revival in 2015, the Badi Baoli holds more than 33 lakh litres of rainwater. This water is used around the year to irrigate the rest of the cultural landscape and ecological zones, and serves as a source of water for any ongoing conservation efforts at the site.

Crafting solutions

The AKTC team researched and collected archival pictures, manuscripts, documents and government records related to the Qutb Shahi tombs to inform their conservation decisions on site.

In one case, a collection of images dating to the 1860s, sourced from the Alkazi Foundation, helped restore the Tomb of Sultan Quli Qutb-ul-Mulk, a revered emperor and the first ruler of the Qutb Shahi dynasty. The tomb structure was modest in size and appearance. But historic photographs revealed intricate stucco work throughout the monument. After dismantling the 20th century plaster on the monument, the original evidence of lime stucco was found, and eventually restored.

The team also built an on-site lime making unit that included devising a huge lime chakki (grinding stone) mounted on a truck engine and motor system to produce the required amount of lime plaster and lime punning of the monuments. The lime was slaked on-site in lime pits with the necessary protective gear, and then stored underwater. The slaked lime was used with different aggregates such as belgiri (wood-apple), sucrose/glucose, gum and natural additives to make the required lime plaster.

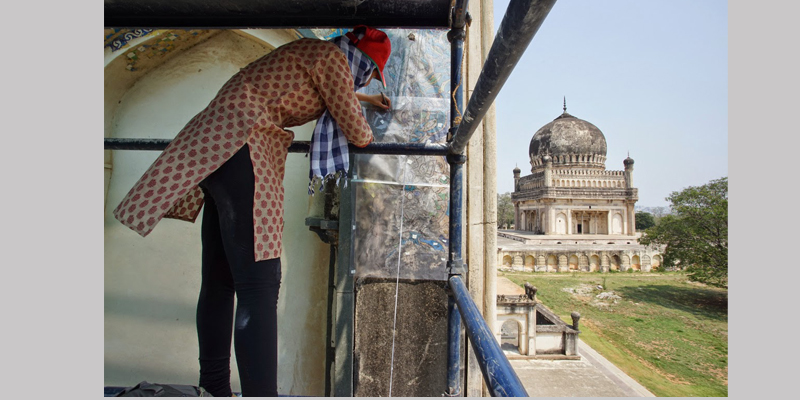

A lot of planning went into some of the restoration initiatives, to ensure the work was completed in an efficient manner. For example, the restoration of the 1600 sq. m dome of the tomb of Mohammad Quli Qutb, the largest single domed structure of the site, began in 2015. In order to successfully complete the plastering of the dome in a short span of time the preparation and planning for the works took months. This involved the erection of a complex scaffolding system around the bulbous dome, and preparing 160 barrels of lime plaster and lime punning. The herculean task was eventually completed using 60 masons and labourers working tirelessly. The final layer of punning was completed under two days.

Since most of the domes on the site are large and bulbous, in the past huge holes were drilled deep into the dome structure to help create scaffolding for the maintenance of these structures. These huge voids were harmful for the structure, and were a source of concern. The AKTC team filled these voids and installed heavy stainless steel chains around the rings of all the domes, to provide easy access in the future and to help regularly de-weed and maintain the domes.

Retaining the essence

Each of the nine buildings conserved under the Tata Trusts’ initiative is unique, and was treated based on evidence found in the historical records and on the site. The elaborate Hamam believed to be built in the 1500s by the founder of the Qutb Shahi dynasty has erroneously been understood to have been a mortuary bath. But with multiple chambers and a large number of cisterns and mechanisms for both hot and cold water, it is indeed the finest Persian type of Hamam to survive in India.

Major alterations and inappropriate 20th century repairs to the structure and its immediate setting had led to a poor understanding and appreciation of the grandeur and complexity of the structures. Clearing out of the overgrown vegetation in the complex, and a careful study of archival photographs revealed a strong link with the Baolis north and west of the structure. It also showed that the water lifting mechanism and underground aqueducts serviced the Hamam till the late 19th century. These have now been restored to their original levels. Removal of cement concrete layers on the roof also revealed a network of terracotta pipes that supplied water to various cisterns at the ground level.

During project implementation, AKTC held external peer reviews with conservation architects, historians, urban planners, archaeologists, and engineers from both private and public organisations. This helped the on-site team better understand the area, its nature and issues while keeping in perspective the national and international standards typically used in conservation.

Time and time again, archival images from the 1860s were used to understand the alterations done on the monuments in the past. In the case of the Tomb of Ibrahim Quli Qutb Shah, for example, the archival pictures showed intricate stucco work done on the petals on the dome, the merlons/kangura (battlements) and other areas on the monument, while also revealing that the late 19th century alterations demolished large portions of the original parapet.

Since the changes were significantly large, it was decided in the 2015 peer review that no attempts to restore the original details would be made. The tomb of Ibrahim Quli Qutb is significant for its intricate glazed tile work. Upon detailed documentation of the tile patterns, there was sufficient evidence to understand that each portion of the external façade had different patterns and hence could not be replicated. The existing tiles on the monument were preserved to prevent further damage and loss of glazed tiles.

A model project

Throughout the project, the role of the craftsmen has been crucial as they played a key role in the conservation project, with each set of craftsmen skilled for a different type of work. For lime, master-craftsmen helped restore the intricate stucco work, while their apprentices worked on plain plastering and punning. Stone craftsmen cut and hand-dressed stones using traditional tools, stone masons built huge masonry walls like the Baoli walls. Workers helped desilt and move soil, and yet another set of workers built the complex scaffoldings that cover the domes and buildings.

The success of this project can be measured in keeping the craft alive by engaging these different categories of master craftsmen and their teams hailing from across West Bengal, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. The project generated over 3,00,000 man-days of work, which directly benefited the craftsmen.

The Qutb Shahi Tombs Heritage Park was nominated to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2016, and is being further developed as an urban Archaeological Park to showcase and ensure long-term preservation, and to enhance the understanding of the 70 monuments that stand within its boundaries. Future connections with the Golconda Fort will allow this site to serve as a starting point for the Qutb Shahi Trail of Hyderabad, leading to significant interest in heritage amongst local citizens and tourists alike.

Image courtesy: Aga Khan Trust for Culture