Bharti Dharasingh Wakode, a young girl from Padegaon in Phaltan taluka of Maharashtra, was asked by her parents to discontinue school after passing Class V as they planned to get her married in a couple of months. Learning about this, a team of volunteers visited Bharti’s home and educated her parents to not only put off the child marriage, but also send Bharti back to school for a brighter future. In March 2017, Bharti enrolled in Class VII and earlier this year, she not only passed to Class VIII, but also stood first in the 100-metre sprint and shotput at the taluka-level sports championship, winning laurels for her school — and doing her parents proud.

Bharti is among the hundreds of children of migrant labourers working in the sugarcane fields, stone quarries and brick kilns in rural Maharashtra, who were spotted under a Tata Trusts project to bring children to the classroom, ensure that they get an education and they do not dropout despite the odds and challenges.

The initiative

Back in January 2015, Paresh Manohar, Programme Officer at Tata Trusts, proposed the concept of ‘Digital Education Guarantee Card’ for children of migrant labourers. On securing support from the Trusts for the initiative, Paresh shifted base to Someshwar Sugar Factory in rural Maharashtra in early 2016 to lead the project from the ground, as a joint effort with the Education Department of Maharashtra, with Janseva Gramin Vikas Pratishthan as the implementing partner and Dhwani, a non-government organisation, as a technical partner.

The maximum drop-out rate is among students of Class I to IV, and more so among girl students, who are made to stay home to take care of their younger siblings or are married off at an early age. And the basic objective of the project was to track each and every child in the 6-14 year age group, and identify issues in mainstreaming the children in schools. Building that mechanism digitally was the first step, under which the children of migrating families are issued a Digital Education Guarantee Card that tracks their education history and enables their future education. The card with an embedded chip tracks migrating children and enables their enrolment in schools near their new address, as well as facilitates compliance with the Right To Education (RTE) Act that makes it mandatory for the government to impart education to children in the age group of 6-14 years.

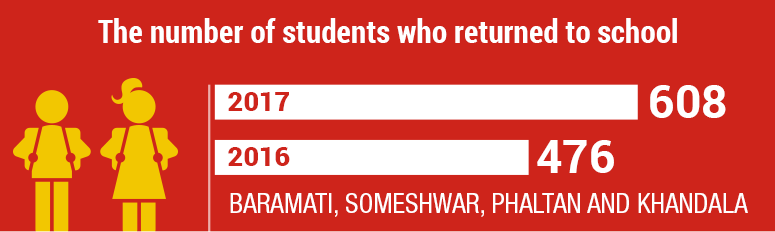

In the early stages of the project, the project leaders and volunteers went to each of the sugar factories, stone quarries and brick kilns in the region, reaching out to the migrant workers employed there and ensuring that their children were enrolled in schools. Besides enabling their admission and initiation in the school, the children are provided books, uniform and other study material. The Trusts also facilitate infrastructure like library, sports equipment, etc. The project has grown from strength to strength, with as many as 476 and 608 students being brought to the classrooms in 2016 and 2017, respectively.

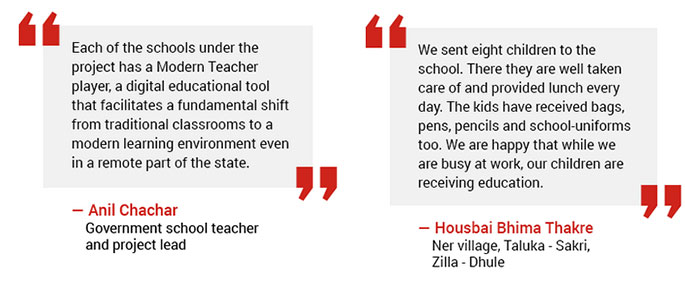

Into its third year, the project covers 80 schools spread across four talukas of Baramati, Someshwar, Phaltan and Khandala. Anil Chachar, a government school teacher leads the team of 35 volunteers across the four talukas of Pune District and works closely with Tata Trusts to ensure efficient implementation of the project. The families of labourers migrate as much as 500km in search of livelihood in rural Maharashtra and the project team’s experience is that once the children are settled firmly in school, not only do they continue their studies but they even give their families a sense of settling down.

The impact

In terms of measuring the social impact of the project, on one hand the committed ownership of the sugar factory, the state education department and the community is indicative of the success and efficiency of the project. On the other hand, the number of children who have entered school in the past two years and the reduced rate of drop-outs are a good measure of the programme’s success. As many as 135 children were spotted randomly on the sites where their parents worked and enrolled into schools. The tracking of children on a daily basis, the active role of school teachers in mainstreaming of children and the community’s efforts to generate funds — as much as Rs15 lakh in the past two years by way of donations from local businesses and individuals — for the initiative, has successfully turned the Tata Trusts’ project into a sustainable model, which can be adopted by the Maharashtra government for implementation in other parts of the state.

Encouraged by the project’s success, Tata Trusts have plans to document and upscale the initiative for greater social impact. Work is underway to build a mechanism for tracking migrant children and to develop standard operating procedures for migrant children’s educational issues, as well as share the learning with the State Education Department to take the project forward on scale.