By Abhishek Puri & Sorun Shishak

|

Cancer, as a lifestyle disease coupled with low awareness, has emerged as one of the major non-communicable diseases with approximately 19.3 million new cases (2020 Globocan estimates). The average annual cancer diagnosis rate in India is increasing at 1.1%-2%. This is alarming as most cases are being diagnosed in the younger economically productive cohort.

The North-East states have the highest cancer incidences and mortality. The state of Assam has 90. 2 affected people per 1 lakh population. The excess mortality (40%-50%) is because of late detection in patients who otherwise incur disproportionate out-of-pocket expenses and high drop-out rates from administered treatment pathways. This was mirrored in the recent “Health of the Nation” report brought out by Apollo Hospital, based on its outpatient data where the median age of diagnosis has become younger. For instance, 30% of colon cancer patients are younger than 50 years.

The Assam government acknowledged the trio of critical issues, namely the lack of infrastructure hindering accessibility, the affordability of treatment protocols, and late detection. Hospitals were ill-equipped to address the chronic burden of care, forcing patients to travel outside the state. The achievement of a significant breakthrough, referred to as the Assam Cancer Model (ACM) by these authors, necessitated a political, policy, and administrative vision to disrupt the negative feedback loops.

This model represents a collaborative effort between the Government of Assam (Assam Cancer Care Foundation) and Tata Trusts, a non-sectarian philanthropic organisation in India that revolutionised cancer healthcare delivery through the establishment of Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai in 1941. Besides healthcare, the Trusts actively work with various communities, positively influencing livelihoods through the creation of self-sustaining ecosystems. The most noteworthy initiatives involve promoting health-seeking behaviour for the screening of oral, breast, and cervical cancers.

The treatment approach

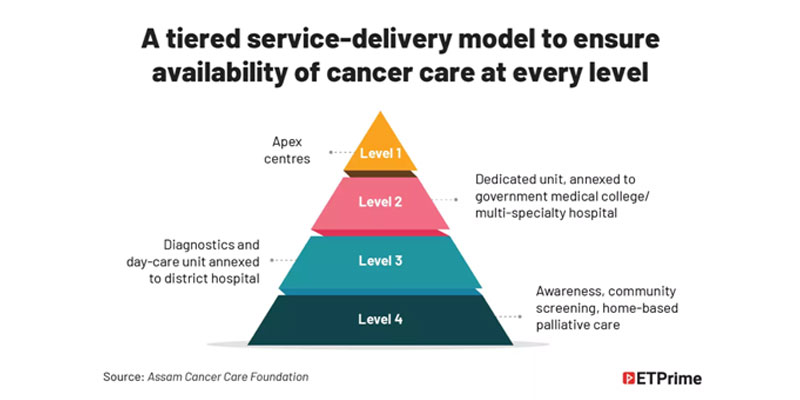

The foundational model (launched in 2018) rests on the quad-level of cancer treatment. L4 is actively involved in the screening of accessible cancers and the provision of home-based palliative care. L3 encompasses diagnostic services and a day-care facility (e.g., radiation therapy, chemotherapy) that is annexed to a district hospital. L2 is an exclusive unit that operates in conjunction with a medical college (equipped with comprehensive oncology services), while L1 stands as the foremost centre of excellence (complete spectra of oncology services, including nuclear medicine and research facilities). The success of this model depends on this system to prevent duplication and ensure cost-effectiveness. In addition, technological initiatives to connect the centres through a unified command would ensure a seamless “platformisation” of healthcare; namely, centralised patient database management, standardised pathology reporting and allow for remote tele-consults.

|

Cancer management requires a fine balance of sequencing between radiation therapy, surgical and medical oncology teams to maximise the therapeutic advantage to patients. It requires an orderly transition to the next level of care after diagnosis and establishing the stage of cancer. Across the board, standardised guidelines and inter-disciplinary consults in “tumour-boards” ensure the best possible outcomes. Therefore, the unified central command would ensure the maximisation of benet and enhance affordability of cancer therapeutics through centralised procurement.

What makes the Assam Model unique

Cancer prevention at one end and follow-up after therapeutic intervention are the two most important pillars of cancer management and success. The episodic model of Indian healthcare, therefore, finds itself stretched out to address these two important determinants of improved outcomes. ACM addresses this by establishing a self-sustaining program through the careful integration of care, quality, and operations, which results in an expandable and collaborative service model. ACM has been structured to scale smaller centres with a focus on prevention, health education, initial diagnosis and, critically, a guided, structured referral to a higher centre to ensure improved disease-free survival. These formative structures can also establish a connection between a state or national- level program that aligns with a specialised focus.

Cash flows are secured throughout the entire process, from inception to the completion of daily administrative tasks, thus ensuring financial viability. Implementing this distributed model guarantees that treatment is administered in familiar community settings, presenting a clear distinction from the centralised approach of apex hospitals that oversee the comprehensive patient journey from diagnosis to treatment.

Implementing innovative concepts such as vendor financing (e.g., extended payment terms over 8-10 years for specialised equipment) and inclusion in state- level insurance programs can establish a financially sustainable framework for other states to replicate.

ACM is presented with daunting challenges when considering its complex geographical locale, varied income levels, and traditional barriers to healthcare- seeking behaviour, including myths surrounding cancer diagnosis and community attitudes towards the disease.

The way ahead

ACM is implementing initiatives to enhance the skills of their workforce through programs accredited by the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) and the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB). The National Cancer Grid, which comprises over 260 cancer centres, plays a crucial role in guiding and ensuring the standardisation of healthcare delivery. In collaboration with the National Health Mission (NHM), ACM has taken steps to execute the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS) in sub-centres (SCs) and health and wellness centres (HWC). They have also established “Swasth Kiosks” (for health screening and awareness camps) and are currently operational in Guwahati, Barpeta, Tezpur, Dibrugarh, Diphu, and Silchar.

There are several expected benefits:

- Reduction in travel time (by over 75%)

- Reduction of out-of-pocket expenditure

- Improving the accessibility to specialist care in community settings.

Consistent community outreach is expected to increase the ratio of early-to-late diagnosis to a manageable 70:30 level.

The outcomes have been remarkably impressive. In a tweet, Assam chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, announced that over 2 lakh patients have undergone treatment since 2022 under the model in the network of 17 hospitals. The state government’s contribution to the project is INR2,460 crore; Tata Trusts have provided INR1,180 crore, Government of India gave INR180 crore and INR80 crore was raised through donations.

The eventual success depends on a comprehensive policy analysis through measurement of the burden of disease, cost-effectiveness of therapeutic interventions, system performance and consumer surveys as a measure of quality control (though not part of this document). This unique initiative has established a mechanism for shared learning and utility for “healthcare-export”. ACM can provide a template for national and international deployment, especially for the Global South, with similar healthcare challenges.

(Dr Abhishek Puri is a practising radiation oncologist and explores intersection of healthcare, policy and technology. He tweets as gammaemitter and maintains Telegram channel for human-curated longform reads. Dr Sorun Shishak is also a practising radiation oncologist.)

This article was first published on 10 April, 2024, The Economics Times