An article by Paroma Sadhana, Tata Trusts, on the sustenance of archives

Archives play an important role for re-visiting the ingredients of history. In its loosest sense, an archive is the collection of bills in your drawer, and in its most vaulted sense, they are the national archives of any country – they protect for posterity and act as blocks for nation building. Archives have engendered several conversations regarding their nature, such as the role of the archivist, its permanence or ephemerality, its digital and/or physical containers, its preservation and safety, access, usage etc. Individuals and organised collectives often seek to build archives around particular themes with the vision that access to these collections will benefit humanity overall by allowing them to understand facets about themes that are not commonly perceived.

Archives play an important role for re-visiting the ingredients of history. In its loosest sense, an archive is the collection of bills in your drawer, and in its most vaulted sense, they are the national archives of any country – they protect for posterity and act as blocks for nation building. Archives have engendered several conversations regarding their nature, such as the role of the archivist, its permanence or ephemerality, its digital and/or physical containers, its preservation and safety, access, usage etc. Individuals and organised collectives often seek to build archives around particular themes with the vision that access to these collections will benefit humanity overall by allowing them to understand facets about themes that are not commonly perceived.

There are no wrong answers when it comes to archives. Moreover, dialogues are endless. But one of the things that is largely non-debatable is that the existence of any archive – individual or institutional – is its ability to be sustainable, and therefore, accessible in the long run.

The sustenance of an archive depends on several factors – its custodianship, its long-term preservation, secure vaults (analog or digital as the case may be) and its usage. If it is agreed that knowledge is power, then archives represent access to knowledge that is capable of not only altering perspectives but also redrafting populist narratives towards the ultimate realisation that history making is, and should be, a collective endeavour.

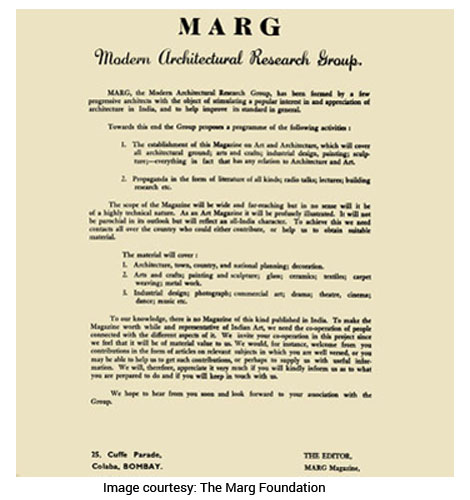

In the first print edition of the Marg magazine, published in 1946, Mulk Raj Anand (the then editor of MARG) writes in his editorial, “It is obvious…that we cannot revive the past in the changed conditions of the present”. Referring to India’s past represented in its architecture, “libraries and museums” the editorial calls for dreaming a new plan for modern India, by critically examining and learning, from its past heritage.

Fast forward 75 years later, the Marg magazines, printed quarterly since 1946, have become a veritable archive of India’s art, architecture and culture. Being the only peer-reviewed magazine on the arts in India, this collection is a rich resource for anyone examining India’s cultural past and present. However, the only way to access these magazines was to procure a print version of them. In 2016, the Marg Foundation embarked on an exercise to digitise the magazines, with the support from Tata Trusts. Print media, nostalgic as it may be, is no longer sustainable without digital strategies to supplement its production. Over a period of five years, and several challenges later, all the magazines were made available on their re-designed website as an archive of the institution and accessible via a subscription fees.

In the case of the Marg Foundation, they were not merely undertaking digitisation, but digitalisation. This enabled the team to better understand the access issues of their magazines, as well as access data on digital usage to devise strategies for further engagement. However, lucrative as digitisation seems, it is not the one-stop solution for print-based archives. In fact in some cases digitisation can be detrimental to the archive’s future. With apps like Cam Scanner or even our mobile phone cameras, making a digital image copy is the fastest way to arrest the archive in time. It is the management and transference of that data, in perpetuity, which poses a significant challenge. With digital formats changing constantly, competitive software creating redundancies of earlier versions and a premium price being paid for cloud storage, digitising one’s collection should be done only when the tangible original collection is secure and stable.

In the case of categories such as ‘public records’ of any office, because of the voluminous nature of the archival material, digitisation becomes more of a curatorial exercise than preservation. Since 1998, the National Archives of India have been digitising their collection with a view to make it accessible. As of 2015, 26 lakh historic public records were uploaded on a website to enable access to scholars. The Public Records Act of 1993 also designates power to weed out and destroy records of ‘ephemeral’ value and decide which records have ‘permanent value’. It is a necessary act, no doubt, to choose archival material for preservation. However in India, given the tempestuous nature of governments, mandates that decree what is important and what should be preserved will wary wildly. It may eradicate subaltern histories altogether, or it may elevate populist narratives in high demand.

While records-based archives should, at some point, delve into digitisation for accessibility, their primary concern should be the preservation of the physical archival material. Digitisation should be the tertiary step in preservation, when the custodian is assured of its benefits and associated costs. In a project from not so long ago, the Trusts supported the Mumbai Police Foundation in the archiving and conservation of their records collection. The records date to the early 1900s, containing papers that shed light on not only the evolution of law and order in Bombay/Mumbai but also facets of the city’s history. Considering the volume of the records, costs of digitisation, and lack of expertise to manage the data generated, it was agreed that digitisation of the records was not the priority.

First, it was decided to conserve and archive the documents (since the records were in varying states of deterioration) so as to allow for future referencing, research and digitisation. However, instead of engaging expert agencies to carry out the work, consultants were engaged instead to train police volunteers in the best practices of archiving and paper conservation. The 28 volunteers were fully trained in paper conservation, building capacity and ownership within the system since these were important aspects for the sustainability of this project. Moreover, properly conserved and housed paper records will last for more than 100 years without significant interventions. Whether digital copies of tangible archives can compete with this timeline, only the future can tell us.

In 2022, we are all archivists of our lives. With the pandemic, the digital has been pushed into over-drive. While digital creation is on the rise as it sends out gazillion bytes of information across the world, digital data can also be overwhelming. Anyone with ‘storage full’ alerts can attest to this. Every day we undertake the act of omission – deleting old files and photos that we deem ‘ephemeral’. Our memories mutate as we scroll through the remainder of our lives stored on phones/laptops/hard disks. Within this context, where we create and delete our own histories, oral history archives, taking ownership of telling one’s story from one’s perspective, are amplified.

Oral history archives can be for just about anything. Because the point of starting is so ordinary – the human – these archives rely on themed categorisation to show commonalities and bifurcations from mainstream narratives about historical events or places. For example, the 1947 Partition Archives- a collection of over 10,000 digital oral histories themed around the Partition of India. An invaluable resource that maps witness stories, largely from the Indian sub-continent, these archives reside entirely on web servers.

The challenge in the sustainability of this kind of archive is not just accessibility, but secure accessibility. Given the nature of the content and to protect the identities of some witnesses, the archive has to ensure that any digital access given is secure and not misused, copied or circulated without consent. The Trusts supported the archive to offer this secure access, through three university libraries, with 26 researchers enabling them to delve into the stories. A digital archive of this kind requires sustained academic enquiry. With departments of history beginning to explore alternate sources of history, and reducing the burden on ‘truth’ and re-focussing on perspectives, oral history archives are becoming an abundant well to draw material from. Sustained collaborations with universities and libraries would allow for archives such as these to thrive and be used by students and scholars alike.

Sustainability can mean different things for different archives – while in some a constant generation of funds might be what is required to keep the archives accessible, in others the question of access becomes paramount.

Archives, unlike their common perception i.e. collection of old stuff, are founts of discovery. How long the fount survives is dependent on how much we, as storytellers, want to keep telling the stories.