Close to near extinction, the Andhra Pradesh-born textile sees a new lease of life

|

| Radha in the Moonlight by Raja Ravi Varma |

The story goes like this: In the 1950s, Bollywood star Nargis Dutt, popularly recognised as the woman in white, received a parcel, which contained a white Venkatagiri sari with a khaddi border. Days later, when Dutt wore the sari for a B-Town party, she received a series of compliments for it. The star of that evening was clearly the sari. A delighted Dutt mailed a letter to the return address, which belonged to Pramadwara Devi of the royal family of Venkatagiri, Andhra Pradesh. In the letter, Dutt thanked Devi for the gracious gesture mentioning that wearing the sari, and receiving compliments for it, was one of her proudest moments.

Venkatagiri saris, known for its airy texture, thanks to its 200 thread count, holds a special place in the royal wardrobe of Venkatagiri. “The saris are worn every day, not just saved for special occasions,” Devi tells Vogue. Venkatagiri is a flatland, with little rainfall. When the family was ruling Venkatagiri about 300 years ago, the royal family gathered weavers and artisans of the land and commissioned them to weave these fine saris and thus the famed saris were birthed and the anni butta technique of weaving was born.

|

About 70 years ago, one sari would set you back by Rs30 or Rs50; “A sari with more intricate work would have set you back by Rs500, says PV Suresh, lead, Venkatagiri cluster, Antaran, a Tata Trusts initiative, dedicated to preserving and promoting traditional Indian crafts.

“Historically, crafts have done well because of patronage—much like the Venkatagiri saris, the weaver cluster of which were supported by the royals. Their skills are valued and feedback is often relayed from consumer to the maker, which in turn encourages the weaver, who puts in numerous hours to create the finished product. But the feedback loop sort of weakened, especially with the Venkatagiri cluster, due to the advent of power looms,” says Mridula Tangirala, Head of Tourism, who also anchors non-farm livelihood initiatives including crafts at Tata Trusts. In around 2021, Antaran, an initiative by Tata Trusts, that works towards strengthening craft ecosystems, identified the Venkatagiri cluster as an existing skill that had been neglected, with potential of revival.

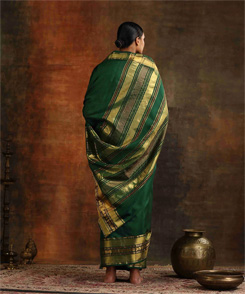

|

| Bottle green pure silk Venkatagiri sari with checks and Pettu border |

According to Pankaj Shah, a mentor at Antaran, Tata Trusts, the craft had potential to be revived as it was geographically closer to the market too. Shah feels that there’s a gap when it comes to crafts revival and the Indian consumer’s awareness. “The Indian consumer still isn’t ready to shell out the right price for a carefully handcrafted or handwoven sari.” Tangirala concurs. She says the gap can be bridged by communication—by narrating to the consumer, how the outfit or saris they wear is made—the man hours that go into crafting one.

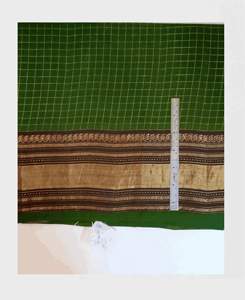

|

| Venkatagiri saree with intricate pettu border details, Khaddi gold band and Benarasi lace, Mutthu-Khaddi and micro-checked body |

A simple Venkatagiri sari, woven using the anni butta technique can take up to two days to be completed. A more intricate sari with traditional motifs like parrots, flowers, leaves and sarada checks can take anything between 10 to 12 days, with a weaver working at a loom for 6-8 hours each day. The current collection features saris in the traditional motifs, as well sarada checks or in solid colours with bordered detailing a rudraksh motif or khaddi borders, which are around two inches broad.

To revive the craft, an IDC or Incubation and Design Centre was set up in Venkatagiri around 2021. And following this the weavers, who had been weaving 60-80 thread count saris, were upskilled and taught to weave saris with higher thread count. “Here’s where the handloom is at an advantage,” says Suresh. For a sari with a higher thread count, the yarn tends to be finer and it would break on a power loom. But not on a handloom.” Hopefully, with these measures, a virtuous circle will emerge, creating a sustainable ecosystem like Tangirala hopes for, putting these saris on the map.

The article was first published on 1 September, 2024 in Vogue India